'An attack on the outlook', Wapke Feenstra (ENG)

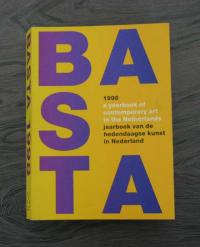

HTV de IJsberg 20 and Basta 1998, a yearbook of Centraal Museum Utrecht NL

Engagement – can you eat it?

Engagement is often about what happens in a far-flung country or about wrongs that we believe shouldn’t be allowed to happen. That’s when we get involved with those far-away places or events and attempt to improve the situation. The other -> there, what you’ve (accidentally) seen or what you’ve heard about, motivates you to take action.

This attitude is founded on a premise of non-acceptance that things just are as they are. In addition there has to be a certain measure of conviction that one is DOING GOOD, otherwise one can’t get motivated. For a good person still commands a deal of respect; one’s reward is not only in heaven.

If this makes you wary that I’m looking to wheedle a donation for a good cause, quoting an account number at the end of this piece, then let me reassure you: this is about art. And, as Q.S. Serafijn of OMMISSION wrote in DECORUM magazine (May 1988), the deal has disappeared from art. Engagement has to do with binding oneself to something. In essence, engagement is a deal. But the deal has disappeared from engagement in the visual arts, and with it, the pay (the gage).

For Serafijn, all that is left is idealism, and one can’t eat that. That’s true – this paper tastes vile, you can take that from me. Even so you have a new (free) edition in front of you. It still exists, that engagement, even without pay. It’s recently been picked up by a number of theorists. They’ve organized a symposium around the theme, entitled COMMITMENT! Engagement in art. (At The Hague’s Museon, May 9, 1998 with artists Ronald Ophuis, Q.S. Serafijn, Sjaak Langenberg, Jeanne van Heeswijk, René Klarenbeek and Frederico D’Orazio. And the art commentators and critics Kitty Zijlmans, Nina Folkersma and Ineke Schwartz. The symposium was organised by the Moderator Foundation). Engagement these days is scaled down and no longer revolves around big issues. It offers a counterweight. Preferably takes place outside the museums and should it hang within the walls of an institution, then it’s shocking; through its depiction, text or execution it works in a confrontational way. Engagement, as has been said, is often concerned with the other. The viewer’s role is also one of redefinition. These days the viewer is left to seek out meaning on his or her own, for the labels are no longer pinned down.

It’s not possible to pinpoint at a distance what’s GOOD in contemporary visual art. And partly because contemporary visual art demands an engagement from the viewer, you often become part of the work of art before having had a moment to choose whether you want to become involved.

Consequently our notions of engagement linked to DOING GOOD will have to change. Involvement in itself transpires to be an autonomous experience, only subject to a possible recap at a later stage. It’s an experience evoked by the staging of the artist – and I’m not just talking about interactive installations and social sculptures here. This scene setting can be anything. Today’s art above all revolves around how this staging works. And it’s good to see that an older art form – the painting – is still alive and kicking, showing that the execution of an image in combination with a theme can still result in a highly engaged viewer. I’m talking about the works of Ronald Ophuis.

He merely wants to create a ‘strong image’ as he frequently repeated ad nauseum in his paper at the symposium. That seems to me to be rather begging the question. A strong image that depicts sexual abuse of small children, or a miscarriage, is more than just a strong image. In a vivid and quite detailed style it depicts a scene that affects me. And it hits me all the more because it’s not real, but staged. It’s been carefully constructed and painted. I see a repugnant action that has been masterfully painted. And I’m left alone with this emotional event on canvas, for the aesthetic force of attraction exerted by the image holds my gaze. It’s no good turning away, the damage is done. The painter’s analysis offers no judgement. I’m given nothing to fasten my gaze. I’m in open communication with the canvas, constantly battling my gaze. The dilemma of looking, the dilemma of the accessory to an event, the dilemma between showing and hiding, the dilemma of the viewer who looks on with his hands in his pockets – all those dilemmas are now fighting in me. I can reproach the artist for that, but that won’t help me: I looked myself and now I’m involved in a touch-and-go situation. It’s a toss-up, and there is no outcome.

It’s because of this that I can really see the atrocities in the picture and it makes me sick.

That kind of engagement on the part of the viewer (me in this case) can be controlled to a certain extent when it comes to paintings, for after all one can turn one’s back. But the projects and changes of role effected by artist Jeanne van Heeswijk allow the viewer no escape. The traditional viewer has been eliminated – one is forced to participate. It’s a case of commitment or running away. In Ronald Ophuis’ paintings you can still sometimes see a victim staring blankly or confusedly into the ‘lens’. Jeanne van Heeswijk’s work eliminates the gaze – and consequently the image too. Her role as a mediator between her own vision and that of others challenges one to participate. A sharp concept and careful staging keeps the projects open-ended. It’s tailor-made work that changes subtly in each new context. Van Heeswijk always works with other people. Even her engagement has become a mediating position. The polarisation between “I and the other” is over. “And” becomes a conjunction and that conjunction becomes the position from which the artist operates. As a consequence, only intersubjectivity exists in the situations staged by Jeanne van Heeswijk. And that’s something – alongside the pictures of Ronald Ophuis – to which I will gladly ally myself.

HTV de IJsberg 20 and Basta 1998, a yearbook of Centraal Museum Utrecht NL

Engagement – can you eat it?

Engagement is often about what happens in a far-flung country or about wrongs that we believe shouldn’t be allowed to happen. That’s when we get involved with those far-away places or events and attempt to improve the situation. The other -> there, what you’ve (accidentally) seen or what you’ve heard about, motivates you to take action.

This attitude is founded on a premise of non-acceptance that things just are as they are. In addition there has to be a certain measure of conviction that one is DOING GOOD, otherwise one can’t get motivated. For a good person still commands a deal of respect; one’s reward is not only in heaven.

If this makes you wary that I’m looking to wheedle a donation for a good cause, quoting an account number at the end of this piece, then let me reassure you: this is about art. And, as Q.S. Serafijn of OMMISSION wrote in DECORUM magazine (May 1988), the deal has disappeared from art. Engagement has to do with binding oneself to something. In essence, engagement is a deal. But the deal has disappeared from engagement in the visual arts, and with it, the pay (the gage).

For Serafijn, all that is left is idealism, and one can’t eat that. That’s true – this paper tastes vile, you can take that from me. Even so you have a new (free) edition in front of you. It still exists, that engagement, even without pay. It’s recently been picked up by a number of theorists. They’ve organized a symposium around the theme, entitled COMMITMENT! Engagement in art. (At The Hague’s Museon, May 9, 1998 with artists Ronald Ophuis, Q.S. Serafijn, Sjaak Langenberg, Jeanne van Heeswijk, René Klarenbeek and Frederico D’Orazio. And the art commentators and critics Kitty Zijlmans, Nina Folkersma and Ineke Schwartz. The symposium was organised by the Moderator Foundation). Engagement these days is scaled down and no longer revolves around big issues. It offers a counterweight. Preferably takes place outside the museums and should it hang within the walls of an institution, then it’s shocking; through its depiction, text or execution it works in a confrontational way. Engagement, as has been said, is often concerned with the other. The viewer’s role is also one of redefinition. These days the viewer is left to seek out meaning on his or her own, for the labels are no longer pinned down.

It’s not possible to pinpoint at a distance what’s GOOD in contemporary visual art. And partly because contemporary visual art demands an engagement from the viewer, you often become part of the work of art before having had a moment to choose whether you want to become involved.

Consequently our notions of engagement linked to DOING GOOD will have to change. Involvement in itself transpires to be an autonomous experience, only subject to a possible recap at a later stage. It’s an experience evoked by the staging of the artist – and I’m not just talking about interactive installations and social sculptures here. This scene setting can be anything. Today’s art above all revolves around how this staging works. And it’s good to see that an older art form – the painting – is still alive and kicking, showing that the execution of an image in combination with a theme can still result in a highly engaged viewer. I’m talking about the works of Ronald Ophuis.

He merely wants to create a ‘strong image’ as he frequently repeated ad nauseum in his paper at the symposium. That seems to me to be rather begging the question. A strong image that depicts sexual abuse of small children, or a miscarriage, is more than just a strong image. In a vivid and quite detailed style it depicts a scene that affects me. And it hits me all the more because it’s not real, but staged. It’s been carefully constructed and painted. I see a repugnant action that has been masterfully painted. And I’m left alone with this emotional event on canvas, for the aesthetic force of attraction exerted by the image holds my gaze. It’s no good turning away, the damage is done. The painter’s analysis offers no judgement. I’m given nothing to fasten my gaze. I’m in open communication with the canvas, constantly battling my gaze. The dilemma of looking, the dilemma of the accessory to an event, the dilemma between showing and hiding, the dilemma of the viewer who looks on with his hands in his pockets – all those dilemmas are now fighting in me. I can reproach the artist for that, but that won’t help me: I looked myself and now I’m involved in a touch-and-go situation. It’s a toss-up, and there is no outcome.

It’s because of this that I can really see the atrocities in the picture and it makes me sick.

That kind of engagement on the part of the viewer (me in this case) can be controlled to a certain extent when it comes to paintings, for after all one can turn one’s back. But the projects and changes of role effected by artist Jeanne van Heeswijk allow the viewer no escape. The traditional viewer has been eliminated – one is forced to participate. It’s a case of commitment or running away. In Ronald Ophuis’ paintings you can still sometimes see a victim staring blankly or confusedly into the ‘lens’. Jeanne van Heeswijk’s work eliminates the gaze – and consequently the image too. Her role as a mediator between her own vision and that of others challenges one to participate. A sharp concept and careful staging keeps the projects open-ended. It’s tailor-made work that changes subtly in each new context. Van Heeswijk always works with other people. Even her engagement has become a mediating position. The polarisation between “I and the other” is over. “And” becomes a conjunction and that conjunction becomes the position from which the artist operates. As a consequence, only intersubjectivity exists in the situations staged by Jeanne van Heeswijk. And that’s something – alongside the pictures of Ronald Ophuis – to which I will gladly ally myself.